Selective Breeding and Husbandry in Cattle part 2

Selective Breeding and the Show Ring

Livestock shows provide a good place for people to go and exhibit the animals they’re most proud of. There’s nothing that isn’t positive about that.

Sometimes though, breeders tend to base their program on what’s currently popular in the show ring. This is antithetical to consistency. Also, depending on what’s currently in vogue, at times, it’s downright destructive to commercial profitability.

A Moving Target

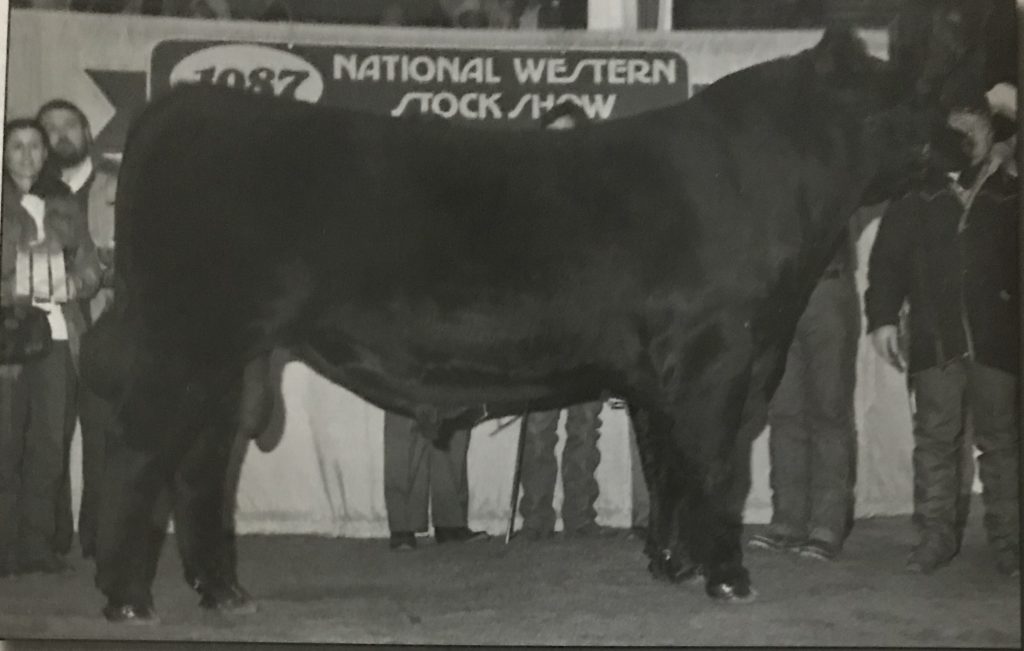

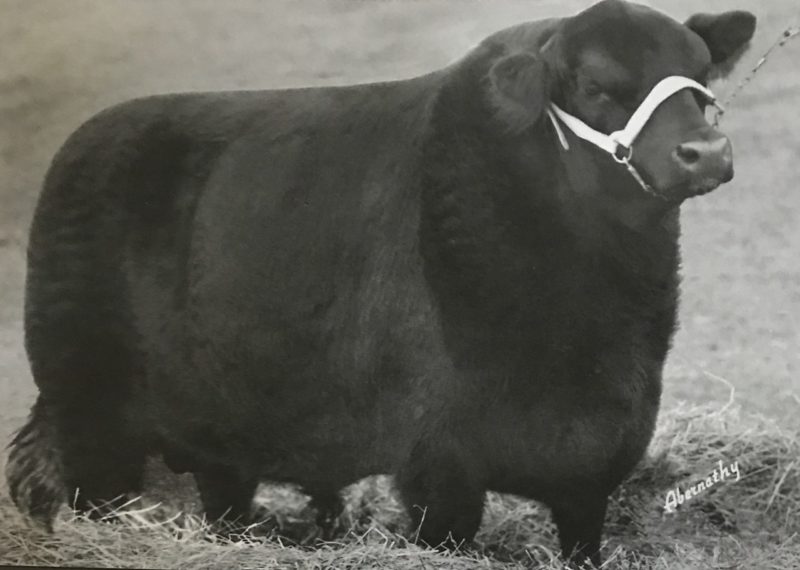

Visualize a timeline of photos of the perceived ideal Angus bull from each year starting in the 1940s through the present day. The 1940s ideal type bull was almost small enough for a tall man to step over his back without getting hung up in the middle. Supposing that same tall man was still around in 1987, he would have just barely been able to peek over the NWSS Grand Champion Angus bull’s back. At the present day, the ideal is somewhere in the middle of those two extremes.

The Birth of the Performance Movement

Today the show ring doesn’t hold near the influence on the seed stock industry that it once did. I believe that’s a change for the better.

Show ring based breeding programs neglected to measure anything of commercial value. Additionally, the phenotypical ideal put out by show judges was a constantly moving target. At times what was popular had little to no relevance to actual production agriculture. Thus, a segment of those in the cattle industry became disillusioned with the eyeball-only method of selecting breeding stock.

Measuring Performance

Keeping and utilizing performance records to make breeding decisions was a far-out idea to some. To others who were considered outside the mainstream at the time, it made perfect sense.

USDA EXPERIMENT STATIONS

As early as the 1920s, USDA experiment stations were investigating the heritability of individual performance in beef cattle.

Some of their early findings were as follows. 1- Beef cattle differ greatly in their ability to grow. 2-These differences are fairly highly heritable. 3- The rate of gain and efficiency of gain are highly correlated. 4-Brood cow performance is a repeatable trait.

BULL TEST STATIONS

The first Beef cattle improvement association was formed in the state of Virginia in 1955. By the early 1970s, every state in the union with a relevant-sized beef cattle population had its own BCIA.

Midland Bull test at Columbus Montana today is the granddaddy of all bull tests. According to the book “Courageous Cattlemen,” the first year of testing at Midland was 1963.

Performance testing was in its infancy. Additionally, breeders of performance cattle were looked upon with some skepticism by those who viewed themselves as being in the ”mainstream”.

In 1963, a grand total of 60 bulls were tested at Midland. Ranchers soon discovered the value a proven performance bull could add to their calf crop, though. Demand has steadily increased ever since.

According to the MBT website, they now test approximately 1100 purebred bulls from over 200 consignors representing more than 32 states each year. The top performing 70% are allowed to go through their sale.

Performance Organizations

Many progressive breeders in the mid-1950s to mid-1960s were interested in attaining standardized procedures for attaining pre and post-weaning performance data on their stock. The ABCPRA, PRI, and BIF were organizations instrumental to that end. Breed Associations have largely taken up this role in present times.

Expected Progeny Differences

Most beef breed associations now collect and use performance data submitted by individual breeders to formulate epds. Epds are a data-based prediction of how far above or below breed average animals’ progeny will be in a given trait.

EPDs provide an estimate as to what an animal’s genetic potential might be, assuming the data behind them is honest. The higher the acc., the more progeny an animal has had measured, and the more reliable the estimate is.

EPDs are a great tool if used combined with intellect. The natural inclination is to strive to have the most when something is measured. In animal breeding, the word most needs to be replaced with optimum.

In part one, I mentioned genetic antagonisms. With cattle breeding, they are ever a part of the equation. For example, a continual emphasis on growth and carcass traits inevitably diminishes a cowherd’s fertility and maternal quality. The cowherd is the factory that everything else hinges upon. Crossing terminal line bulls on a maternally bred cowherd makes the most sense to the commercial man. I’ll talk more about that in part 3.

Genomics

Genetic testing in beef cattle has come a long way. Lethal recessive genetic defects are now detected with a simple blood test.

Genomic testing also enables us to determine degrees of genetic relationship. When enough genetic profiles are submitted and the information is combined with epds, it theoretically makes the epds more accurate on individual animals.

Potential Problems in Breeding by the Numbers

Performance data based selective breeding decisions are superior to any subjective method. It can have its own setbacks, though.

In the year 2018, we live a life of ease. We have the world before us with the click of a mouse or a swipe on a smartphone. Whatever isn’t in front of us immediately can be delivered in a couple of days, thanks to Amazon. It’s seductive for aspiring breeders to think that EPDs somehow provide a shortcut to becoming a cattle breeder. EPDs are a great tool, but a breeding program based solely on numbers is a recipe for failure.

Poor Structure

I’m sure you’ve heard the saying pretty is as pretty does. It’s a saying tailor-made for numbers breeders.

These days, cattle with sway backs and high tail heads are certainly plentiful in the Angus Journal. An upturned pelvis translates into calving problems.

One of the advantages cattle have over pigs and poultry is that they convert low-quality cellulose found in grassland and range country into high-quality protein. Structurally unbalanced cattle aren’t suited to travel long distances in range country. Range cattle need to be able to maintain themselves with little or no human intervention. Consequently, proper foot and leg set and skeletal structure are vitally important.

She Bulls

Another consequence of breeding exclusively by the numbers worth mentioning is the lack of masculinity in today’s highly touted AI sires. In particular, selective breeding exclusively for stacked carcass numbers seems to result in a large percentage of she bulls. Some of these critters resemble Holstein steers more closely than Angus bulls. Aside from being difficult to look at, lack of sex character speaks to lack of fertility. This also goes for cows that look bully.

AI

Before the late 1960s, the American Angus Association had an owned bull rule. You couldn’t register animals to an Angus bull unless you owned him. Some breeders were finding ways to get around this. This caused somewhat of a scandal for the Angus Association. A group of breeders led by Martin Jorgensen filed a complaint alleging unfair practice and preferential treatment before the Justice Department. The Angus Association eventually relented and did away with the ownership rule. The result is that we now have open AI with the restriction that you must buy an AI certificate with each registration.

With open AI, a breeder can now use any AI sire they choose. An individual no longer needs to have a lot of money and influence to use the most sought-after bulls of the breed. The AI industry generates millions of dollars for both breeders and AI companies.

Some Possible Problems That Come With AI

AIing is just another tool in a cattle breeder’s box. If it’s used with a healthy dose of discipline, it’s an empowering one.

There’s a big temptation, though, to use every new highly promoted sire that comes down the pike just because you can. That’s where the discipline comes in. Excessive sampling creates randomness.

Seedstock should be predictable. Predictability comes from formulating a disciplined breeding plan and sticking to it.

A breeder should have the confidence to stand on his own convictions and, at times, to stand out from the crowd. A large share of Angus breeders uses the same AI sires as their competitors. This is a fact easily discovered through the study of any Angus Journal. This is largely due to the marketing aspect of the business. I’m not criticizing it. I’m only saying that if you’re doing what the crowd is doing, you shouldn’t expect any better results than what the crowd gets.

That’s all for this week. Thanks for taking the time to read this. I may have ruffled a few feathers. If I’ve ruffled yours, take a breath and realize that the opinions expressed are mine. They don’t necessarily have to be yours. I also need to acknowledge that there are other cattle breeds out there besides Angus. I’ve written from an Angus breeder’s perspective because that’s what I have a little bit of background in.

The Contrasting Angus bull pictures came from “Angus Legends.” Information on the book is located on The American Angus Hall of Fame website.

I obtained the vast majority of whatever background information I used this time around from the book “Courageous Cattlemen.”

Stay tuned for part three.